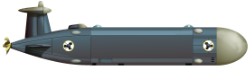

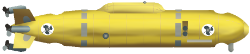

Theseus AUV

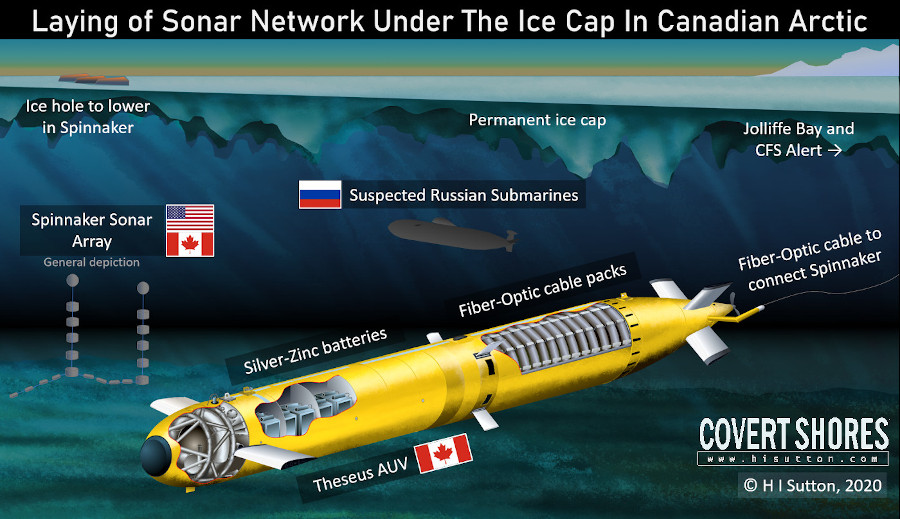

During the Cold War, NATO believed that Russian submarines were using the ice cap in the Canadian Arctic as cover to covertly move between the Atlantic and Pacific. So the U.S. and Canada placed a special sonar network there, deep under the ice. Canadian engineers had to build the world’s largest autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), Theseus, to lay a cable where ships could not reach.

During the Cold War, NATO believed that Russian submarines were using the ice cap in the Canadian Arctic as cover to covertly move between the Atlantic and Pacific. So the U.S. and Canada placed a special sonar network there, deep under the ice. Canadian engineers had to build the world’s largest autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), Theseus, to lay a cable where ships could not reach.

Original artwork. CLICK for high-resolution image.

The project started in the 1980s, at a time when Russian submarines were getting much quieter. To listen for them, a joint U.S. and Canadian sonar array was to be placed several hundred miles north of the remote Canadian base at CFS Alert. The array was codenamed Spinnaker, in honor of the bar where scientists made many of the unclassified decisions in the project. This was similar to the now-famous SOSUS (Sound Surveillance System), but used classified technology to match its operational circumstances. In fact it must have been much more advanced than the original SOSUS.

The ultimate book of Special Forces subs Covert Shores 2nd Edition is the ONLY world history of naval Special Forces, their missions and their specialist vehicles. SEALs, SBS, COMSUBIN, Sh-13, Spetsnaz, Kampfschwimmers, Commando Hubert, 4RR and many more.

Check it out on Amazon

Connecting the sonar array to the base would require laying a fiber-optic cable for hundreds of miles under permanent ice cap. The solution was to build the world’s largest autonomous underwater vehicle. The uncrewed submarine would swim from an ice hole nearer to the base all the way to the Spinnaker array. As it went the cable would unreel out of the back. Thus ‘Theseus’ got its name from the mythical hero of Ancient Greece who trailed thread behind him when he ventured into the labyrinth to fight the Minotaur.

The Theseus AUV, an uncrewed submarine, sits ready to be lowered through an ice hole. The person sitting in the background shows the scale of it. Credit BRUCE BUTLER

Theseus was built by International Submarine Engineering (ISE: website) who had already built under-ice AUVs. Cable-laying was proven on the smaller Autonomous Remotely-Controlled Submersible (ARCS) before the extra-large Theseus was built.

When we think of advanced Canadian military projects which were ahead of their time, the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow springs to mind. That delta-winged Mach-2 fighter flew in the 1950s and was cutting edge technology at the time, one of the all-time great aircraft. But it was cancelled abruptly in 1959 before it could enter service. The Theseus AUV is up there with the Avro Arrow, but less well recognized. And unlike the Arrow, it was used operationally, in one of the boldest projects started during the Cold War.

The project had many secret aspects. Years later much of what we know about the project comes from Bruce Butler, one of the core team involved. Bulter has written a book, Into the Labyrinth (Butler's book website), and recently talked to the Underwater Technology Podcast about the project.

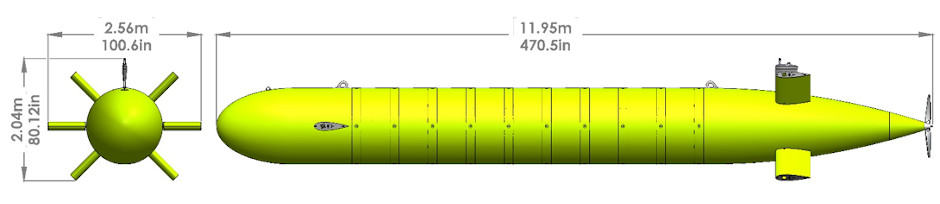

Image: ISE

The design had the batteries and electronics in a sealed compartment similar to a regular single-hulled submarine. The batteries were silver-zinc, but since these were expensive and fragile traditional lead-acid batteries were used during some tests. Unlike most other AUVs the extra-large Theseus had ballast tanks fore and aft. These were annular, similar to on some SDVs.

The cable packs were in a large payload section behind the battery/electronics compartment. The payload area was flooded but each cable reel had its own compensation tank wrapped around it. As the cable spooled out the tanks were flooded to compensate for the reduced weight.

The World's ONLY Guide to

Narco Submarines

10 years of research, analyzing over 160 incidents, condensed into a handy guide. This unique book systematically breaks down the types and families. With detailed taxonomy, recognition 3-views, profiles and photos. Available on Amazon

Theseus was 35 feet long and about 4 feet across. In AUV terms this is large, even today. In modern naval terminology it would be categorized as a large-displacement uncrewed underwater vehicle (LDUUV).

The Spinnaker sonar system was placed on the sea floor right on the edge of the arctic shelf. It was about 84 degrees north, up in the top right-hand corner of Canada, near to Greenland. Such an advanced project took years to realize, so it was not until spring 1996 when Theseus could go to work laying the cable. The whole operation was pushing the boundaries of uncrewed underwater vehicles at the time. Despite some close calls along the way, Theseus was able to navigate to the Spinnaker, letting out the vital thread as it went.

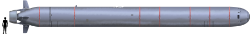

Get The essential guide to World Submarines

This Covert Shores Recognition Guide Covers over 80 classes of submarines including all types currently in service with World Navies.Check it out on Amazon

Many details of the project and technology involved are still classified. And we may never know whether Spinnaker ever picked up any Russian submarines. By the time it had been laid the Russian Navy was in steep decline following the end of the Cold War.

But with a resurgent Russian Navy today, the relevance of systems like Spinnaker may be greater than ever. And one of the roles which large submarine drones like the Orca might do is lay cables on the sea floor, unseen from above. Historical precedents like Theseaus can help us understand the way that these might be employed, and the challenges that they will face.

Image: ISE

Related articles (Full index of popular Covert Shores articles)

Iranian XLUUV

Iranian XLUUV

NMRS UUV captured by North Korea

NMRS UUV captured by North Korea

XLUUV armed extra-large UUV

XLUUV armed extra-large UUV

Chinese HSU-001 LDUUV

Chinese HSU-001 LDUUV

Garmoniya-GUIDE AUV

Garmoniya-GUIDE AUV

ASWUUV anti-submarine unmanned underwater vehicle

ASWUUV anti-submarine unmanned underwater vehicle

Biomimetic Underwater Vehicles

Biomimetic Underwater Vehicles

Poseidon Intercontinental Nuclear-Powered Nuclear-Armed Autonomous Torpedo, and countering it

Poseidon Intercontinental Nuclear-Powered Nuclear-Armed Autonomous Torpedo, and countering it

Russian Navy Beluga whale

Russian Navy Beluga whale

Harpsichord (Klavesin) AUV

Harpsichord (Klavesin) AUV

SwarmDiver micro-USV

SwarmDiver micro-USV

Nerpa anti-diver UUV

Nerpa anti-diver UUV

Cephalopod armed extra-large UUV

Cephalopod armed extra-large UUV

Flag  Lun Class Ekranoplan (Wings in Ground Effect) w/Cutaway

Lun Class Ekranoplan (Wings in Ground Effect) w/Cutaway