This article draws heavily on the research of others, in particular The Historical Diving Society (HDS) and also Robert Hobson, author of (Chariots of War (Amazon)). Sincere thanks to everybody who has helped.

This article draws heavily on the research of others, in particular The Historical Diving Society (HDS) and also Robert Hobson, author of (Chariots of War (Amazon)). Sincere thanks to everybody who has helped.

Information and corrections welcome. Contact the author HERE

The forgotten British SDV: Chariot Mk.II

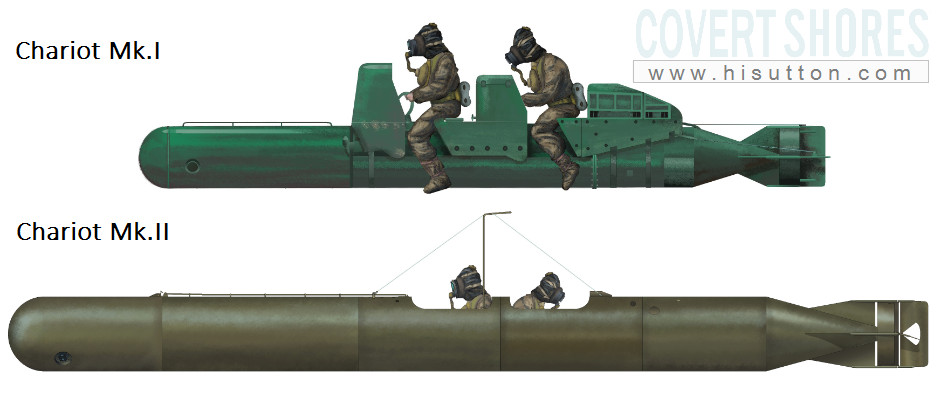

The Chariot Mk.II (aka Terry after its designer) is a forgotten hero of World War Two British midget submarines. It was kept secret and remained in service after the war, whereas the older Chariot Mk.I was revealed to the public in 1944. Consequently the popular imagination of a ‘Chariot’ is the Mk.I with the two divers riding astride a torpedo-like object.

The Chariot Mk.II (aka Terry after its designer) is a forgotten hero of World War Two British midget submarines. It was kept secret and remained in service after the war, whereas the older Chariot Mk.I was revealed to the public in 1944. Consequently the popular imagination of a ‘Chariot’ is the Mk.I with the two divers riding astride a torpedo-like object.

The Mk.I had been hastily built and introduced to service in 1942 as a direct response to the Italian SLC (Siluro a Lunga Corsa, Long Running Torpedo) which had sunk two British battleships in Alexandria on 20th December 1941. Churchill famously reacted:

“Please report what is being done to emulate the exploits of the Italians in Alexandria Harbour and similar methods of this kind. At the beginning of the war Colonel Jeffries had a number of bright ideas on this subject, which received very little encouragement. Is there any reason why we should be incapable of the same scientific aggressive action the Italians have shown? One would have thought we should have been in the lead. Please state the exact position.”

The immediate response was to copy the SLC in its entirety, albeit using British components throughout. However work soon started on a completely fresh design which became the Chariot Mk.II

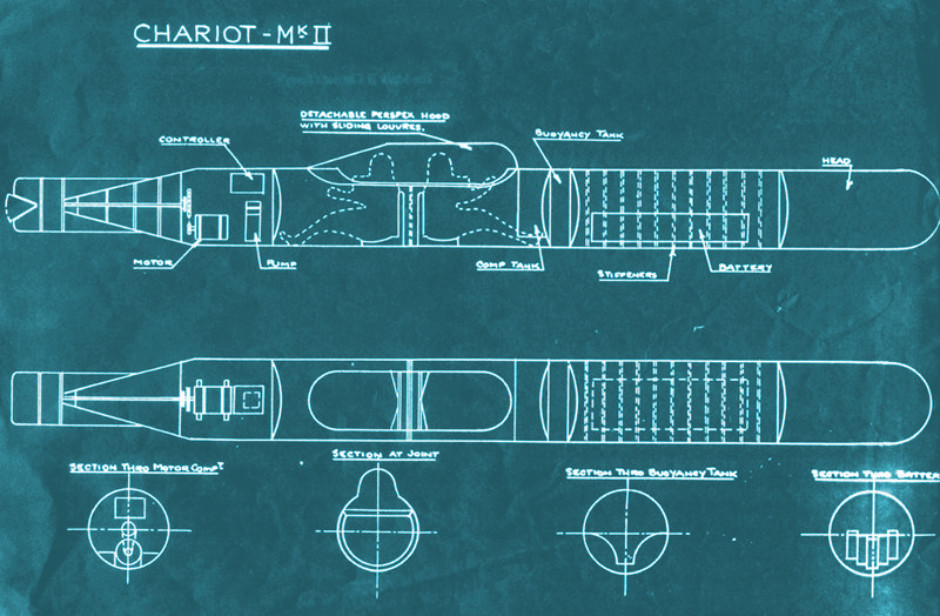

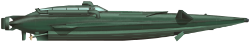

The main visible difference was that the crew sat inside the hull of the Chariot Mk.II instead of riding astride it. To reduce drag the crewmen sat back-to-back with the second crewman facig backwards. The hull had a larger diameter to allow this. Less obvious, but more significant, was that the Chariot Mk.II was much more strongly built. This allowed it to be carried externally by a submarine instead of requiring sealed containers to be bolted onto the outside of the host submarine. It was also much longer and carried a larger 1,000lb (450kg) warhead on the nose.

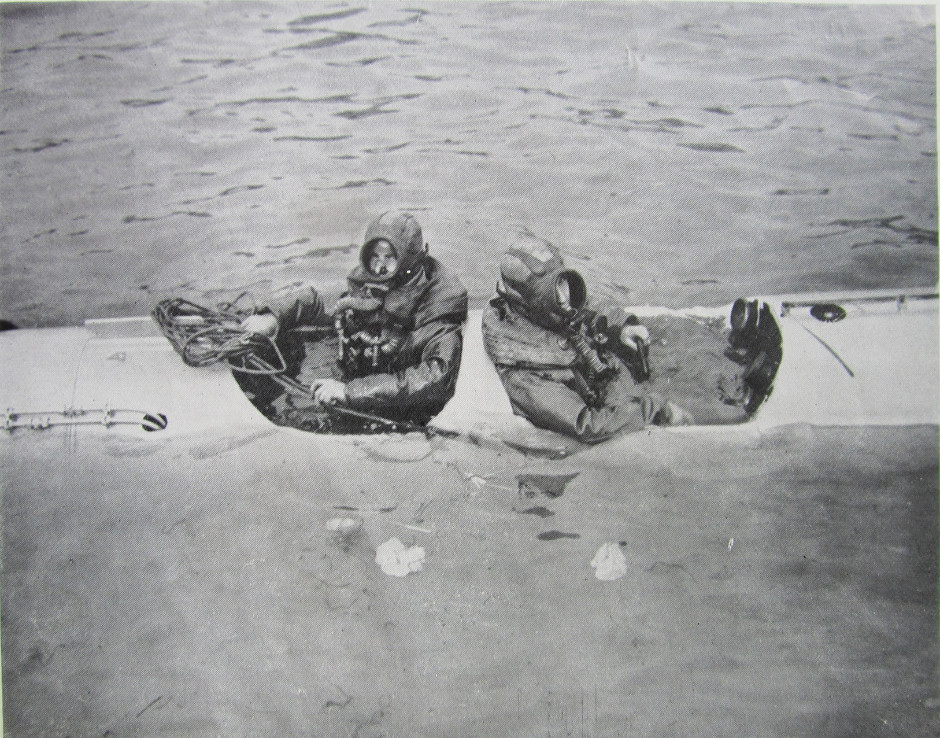

The two crew, who had to wear breathing apparatus (rebreathers), sat back-to-back. This photo is from 1950. Source The Historical Diving Society (HDS)

The cockpit of the Chariot Mk.II. The frame could be raised to protect the crew while passing through anti-torpedo nets and boom defenses.

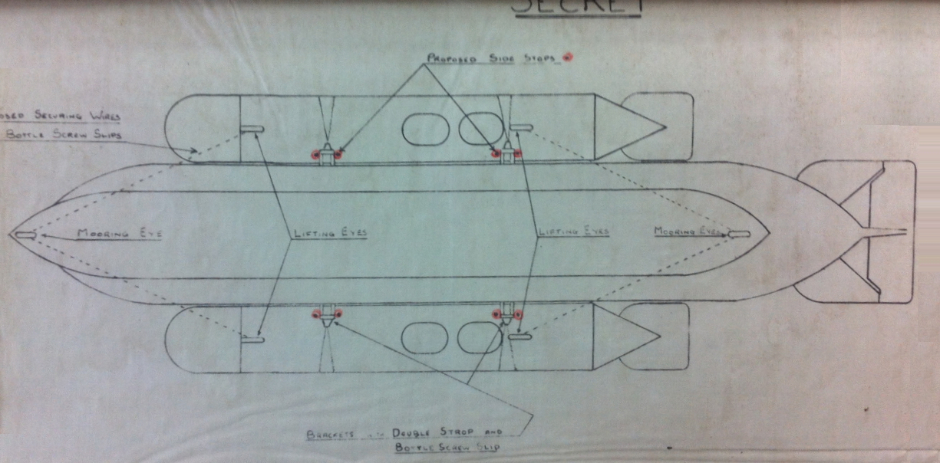

Early plans. The cockpit canopy was never fitted. Source: Robert Hobson

The ultimate book of Special Forces subs Covert Shores 2nd Edition is the ONLY world history of naval Special Forces, their missions and their specialist vehicles. SEALs, SBS, COMSUBIN, Sh-13, Spetsnaz, Kampfschwimmers, Commando Hubert, 4RR and many more.

Check it out on Amazon

Combined Operations Pilotage Parties (COPP)

A vital task for Allied Special Forces during World War Two was covert beach reconnaissance. The British Combined Operations Pilotage Parties (COPP) had been established in November 1942 and the first teams being rushed into service in the Mediterranean and more units undergoing more extensive training in UK where they set up base on Hayling Island on the South Coast, at the other end of the country to the secret bases in Scotland. Their main means of transport were two-man canoes. The teams were dropped off by submarine and paddle close inshore before one man got out and waded ashore, taking the wide range of specialist soil sampling and measuring gadgets required to do the job properly.

However, a lot of the canoes did not return to the host submarines. These early losses were chalked up to being spotted by enemy sentries, so Chariot Mk.IIs were rapidly introduced to provide a more covert approach. The basic method was for the Chariot to be launched from a surfaced submarine about six miles offshore, and then proceed to within a mile of the shore from where it would be bottomed (assuming the water was shallow enough) and the pilot would walk ashore reeling out a wire. On his return he felt along the wire, taking soundings at set intervals marked by blobs on the wire. There was a plan for him to carry a modified torpedo depth and roll device modified to record the depth when it ran for about five seconds at each of the set intervals.

They found that its advantage of stealth was more than outweighed by the fact that the Chariot was relatively blind and could not tell if it was taking accurate soundings because it tended to drift sideways in the current. And the Chariot could only take one line of soundings during the mission, but a canoe team could take 3-6.

At any rate, the distance from shore at which the canoe had to stop was considered the safest part of a COPP mission. The Chariots also needed to be taken aboard the submarine and returned to base for charging and maintenance between missions. Canoes were still required to guide the Chariots to the beach because the Chariot lacked the navigation gear and radios, and then guide them back to the mother submarine. If the Chariot failed to ‘home’ in on the submarine (known as a miscarriage), it was invariably lost, whereas a canoe team could lay-up ashore and try again the next night. In addition, the canoeists were commando trained and armed, whereas the Charioteers were unarmed and in cumbersome dry suits.

In operations, four Chariots were lost or damaged due to weather and launching accidents so it is no surprise that canoes were considered much more practical.

Attack

The Chariot Mk.II’s baptism of fire came in October 1944. With too few targets left in Europe, the Charioteers were deployed to the Far East. On 20th October the submarine HMS Trenchant left Ceylon aiming for the port of Phuket in Thailand. Two Mk.IIs were strapped to her ballast tanks either side of the conning tower.

HMS Trenchant (P331), a T-Clas submarine.

The Chariots were launched at 2200hrs on 27th October some 6.5miles from the harbor entrance. Each Chariot had a nickname and a specific target; Tiny was to attack the a troop transport Sumatra Maru, and Slasher was to attack a smaller ship, the Volpi.

It was an almost textbook attack with both Chariots finding their targets and laying their charges. And then in stark contrast to earlier human torpedo attacks they returned to the waiting submarine some five hours later. The submarine captain ordered them to be scuttled as a Japanese patrol boat had been heard in the vicinity. Two hours later, the targets blew up, marking the last British Chariot operation of the war.

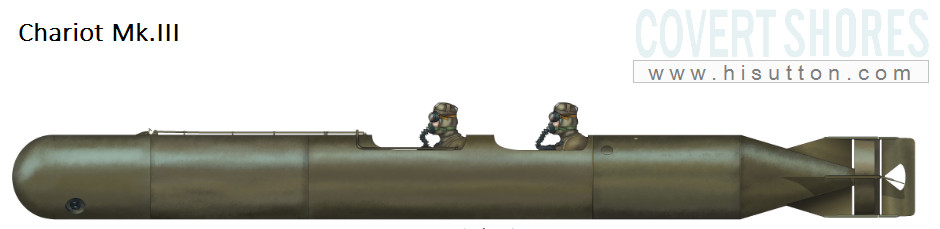

Chariot Mk.III

There were several attempts at a follow-on “Chariot Mk.3”. One was a local effort by the men responsible for training Charioteers aboard the submarine depot ship HMS Titania and involved reducing the diameter by 3 inches to 2.25ft (0.7m), and length by 5ft to 25.5ft (7.8m) which was still noticeably longer than the Chariot Mk.I. The seating arrangement was also changed so that both men faced forward.

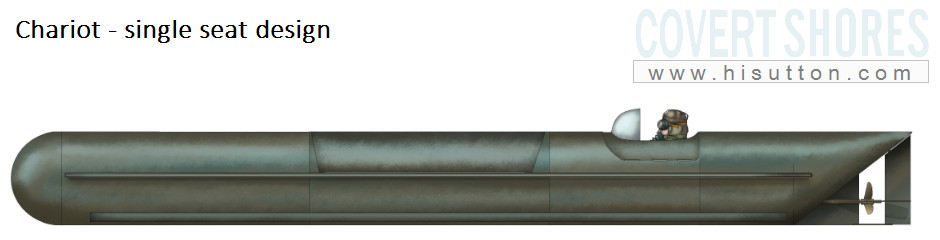

Single-man Chariot

Another interesting variation was a single-seat Chariot with a completely changed aft section and ‘lobster pot’ multiple charges instead of a single larger charge. Unusually the charges were carried between the crew section and the battery compartment which was in the nose where the warhead normally was. This meant the charges had to released vertically, either upwards or downwards. Length was significantly shorter thanks to the removal of the second cockpit at 24.5 ft (7.4m) but diameter remained unchanged at 2.6ft (0.8m). The design is in some way similar to the Sleeping Beauty and may have been influenced by it. Beyond this much, very little is known of either craft. Research thanks to Robert Hobson, author of (Chariots of War (Amazon)).

Post war service

There were only six serviceable Chariot Mk.IIs left in the UK at the end of the war and by 1950 there were even fewer. With the post war defense cuts there was no serious consideration of procuring more. They were kept in limited service however and operated by Royal Navy Clearance Divers. The main tactical development was a plan to launch the Chariots against Soviet harbors from X-Craft midget submarines in the event of World War Three. A test was carried out with XE-7 in October 1950. Two Chariots were attached to the outside of the X-Craft in place of the ‘side charges’. This configuration gave the X-Craft a stand-off capability. Although the tests were considered successful, the configuration was never fully operationalized.

Chariot Mk.II with warhead section removed. Source: The Historical Diving Society (HDS)

Not on your Nellie

Source: Lt. Bob Lusty, RNCDO (Ret)

By the 1950s the Royal Navy divers were organized into the Clearance Diving Branch which, as the name implies, was focused on mine clearance as a continuation of the wartime Port-Parties who cleared Europe’s ports of mines left by the retreating Axis forces. They were less focused on offensive capability. That is not to say, however, that a serious offensive capability wasn’t maintained for many years particularly in the ‘Home Service’ units. It was however felt that swimmers stood a better chance of getting through defenses due to the relative noisiness of the submersibles at the time.

So the remaining Chariots were therefore experimented with for mine clearance purposes. The basic premise, as with many underwater craft at this time, was to use them simply as a means of propulsion, increasing the endurance and speed of the divers. Earlier trials with a regular Sleeping Beauty were hopeful, but that craft proved to be too small to comfortably carry a spotter. So some of the larger Chariots were modified with a third cockpit in the nose instead the explosive charge. This was provided with a watersheild, as was the main cockpit. Additional hydroplanes were added to improve control and impact bars were also fitted.

A modified Chariot Mk.II, pictured in 1957-8. Source: The Historical Diving Society (HDS)

The new craft were christened Nellie.

Source: The Historical Diving Society (HDS)

Source: The Historical Diving Society (HDS)

Further modifications

The Royal Navy Clearance Divers modified another Chariot in a similar way to Nellie but with a cupola in the bow. This must have been retired by mid-1960s.

Source: Cdr. John Grattan, RNCDO (Ret)

Source: Cdr. John Grattan, RNCDO (Ret)

Source: Cdr. John Grattan, RNCDO (Ret)

Related articles (Full index of popular Covert Shores articles)

British SDV developmemts in 1960s (Dick Tuson)

British SDV developmemts in 1960s (Dick Tuson)

SDV Mk.9 SEAL Delivery Vehicle

SDV Mk.9 SEAL Delivery Vehicle

DGSE's SDVs

DGSE's SDVs

Cos.Mo.S Nessie Fast SDV submersible boat

Cos.Mo.S Nessie Fast SDV submersible boat

Cos.Mo.S CE2F chariot

Cos.Mo.S CE2F chariot

SubSEAL advanced SDV

SubSEAL advanced SDV

Sleeping Beauty (Motorised Submersible Canoe) of WW2

Sleeping Beauty (Motorised Submersible Canoe) of WW2

SubCat SDV

SubCat SDV

Gabler Sea Devil Swimmer Delivery Vehicle

Gabler Sea Devil Swimmer Delivery Vehicle

Vogo 'Chariot' SDVs (SDV-300, SDV-340...)

Vogo 'Chariot' SDVs (SDV-300, SDV-340...)

Triton-NN Submersible Boat

Triton-NN Submersible Boat

Marex Type-A (A2, A4, A5, Comex Total-Sub-01) SDVs

Marex Type-A (A2, A4, A5, Comex Total-Sub-01) SDVs

THE book on Special Forces subs Covert Shores 2nd Edition. A world history of naval Special Forces, their missions and their specialist vehicles. SEALs, SBS, COMSUBIN, Sh-13, Spetsnaz, Kampfschwimmers, Commando Hubert, 4RR and many more.

Check it out on Amazon